Film of The Same Name

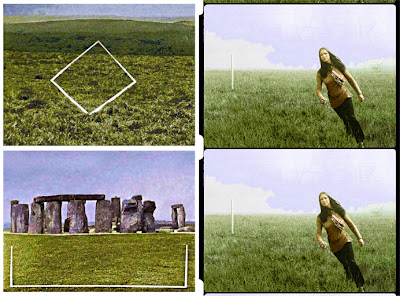

Film of The Same Name follows Philip Sanderson and Steven Ball as they revisit the haunted landscapes of their 1980s film trilogy Apostrophe S. The film melds the filmmakers' revisiting of the locations of the original films, a workshop re-enactment, and topographic animation, all set to a soundtrack of newly composed songs and music with fragmentary echoes of the earlier films.

Sunday, October 8, 2017

Tuesday, September 15, 2015

Song from Film of the Same Name

Song from The Film of The Same NameSong from The Film of The Same Name by Sanderson & Ball

Posted by Storm Bugs on Sunday, June 21, 2015

Thursday, August 27, 2015

The path starts here

Tuesday, October 21, 2014

Listen Hard - FotSN with William English on Wavelength

Wednesday, August 13, 2014

A mislaid shoe leads to a funny gate

With Leigh Milsom and William Fowler reviving the original actors' performances of the ghost of a woman who dies in a car accident, and the ghost hunter who pursues her, the film becomes a cinematic revenant as elusive and intriguing as those it returns to.

The original Apostrophe S trilogy comprising: A Postcard from Boxley Hill, Green on the Horizon and Hangway Turning which were all shot on Super 8 then edited on video, predates and to some extent predicts the recent vogue for artist films which combine documentary and experimental filmmaking techniques, and the phenomenon that has become known as 'hauntology'.

Monday, July 7, 2014

Green on the BFI

Tuesday, February 26, 2013

Monday, November 26, 2012

Advice for prospective participants

Your participation will take you through a process criss-crossed by indecision, contradiction and contingency; dotted with historical citation, reenactment, projections of new and archival material, disembodied narration, and disconnected dialogue. There is no reliable plan for this process, a number of distinct sections have been identified, however it appears the relative ordering of these sections changes depending on the approach taken.

Observations on these changing sections are contained in the blog, which you will find at http://filmofthesamename.blogspot.co.uk. This should help you when performing in one section or another. The blog posts are in no particular order and must be used at your discretion.

This is not a game or competition. There are no fees being paid, deadlines to meet, or scripts to follow. You are on your own. The starting point is the mid nineteen-eighties and the films that make up the Apostrophe-S trilogy, your destination Film of the Same Name in the mid two-thousand-and-tens.

Friday, September 7, 2012

Green on the Horizon theme whistled

recorded in St. Mary's Church, Higham Ferrers

on the edge of Cliffe Marshes

25 January 2011

Thursday, August 30, 2012

Tuesday, August 7, 2012

kinematopography

There was much talk of texts being read to camera and even designs for a more developed musical element “a concept video” no less. I broached the subject of how the project had developed since we last met, as it was still unclear to me as to whether FoTSN is to be a remake of the original Apostrophe S project or a film about the remaking or possible remakings. Perhaps unsurprisingly the answer “both” came back.

As the evening wore on though I did get a glimpse of some possible structure to the project. Sanderson waived round a copy of Finding your way on land and sea by Harold Gatty. I am familiar with Gatty’s work reprinted in several volumes with similar titles, which essentially offers an insight on how to navigate terrain without map or compass. Gatty draws on techniques used by indigenous people such as using sound, smell, wind direction as a means of orientating oneself. Gatty’s text is quite sober and practical; keen to dispel any motions of some primitive sixth sense. In doing so it recognizes however that the conception of space as understood or explored by indigenous people may well differ from that in the west.

At the point in the conversation I was able to introduce some of my own recent reading in the area in particular a paper by By Claudio Aporta Inuit orienting: Traveling along familiar horizons. Aporta’s analysis of indigenous people navigate and orientate themselves in space is not fundamentally different from Gatty’s however another dimension is introduced that of memory and emotional attachment. With the addition of memory and a sense of place that builds on generations of knowledge and travelling cognitive maps “a person’s organized representation of some part of the spatial environment” (Downs and Stea 1977: 6) become memoryscapes.“Quite” said Sanderson, “indeed” said Ball but “we are not making a film about indigenous memoryscapes’ but “rather” interrupted Sanderson excitedly “how media representation of space can create something akin or analogous to an indigenous memorysacpe”. “If” said Ball seriously (or as seriously as he could be after goodness know how many beers) “ media and in this instance the original film of Green on the Horizon act as the fifth dimensional element to create”, “a memorymediascape, a sort of kinematopography” interrupted Sanderson. “A little cumbersome perhaps” said Ball “but essentially yes”. Marcus Lumen

Monday, August 8, 2011

Sunday, August 7, 2011

Tuesday, July 5, 2011

Kit's Coty/Bluebell Hill ghost hunts reported

|

| Orb (light anomaly) captured at Kit's Coty ghost hunt |

Assignment one

Saturday, June 25, 2011

T C Lethbridge

Tuesday, May 24, 2011

On Pylons

| Sun behind pylon |

Their aesthetic appeal is as great aloof public found sculptural objects, literally carrying a great invisible power, aerial ley-lines rooted to the ground and yet unscalable, emitting the low hum of electricity like some gigantic electric aeolian harp.

Pylons come in various designs, the ones populating Cliffe Marshes would appear to be of the L2 and L6 type.

Pylons have become as much a part of the British rural landscape as any ostensibly 'natural' feature. The current electricity pylons, first chosen in 1929, are designed to be strong against high winds and capable of carrying the load and tension of cables. The name 'pylon' comes from their basic shape, an obelisk-like structure which tapers toward the top.

There are plans afoot to redesign pylons, a move that could have the most significant impact on the appearance of the British landscape since the enclosure.

Friday, May 13, 2011

Thomas Cubitt

1. Surely those concrete pillars are marked on the map as 'Limekilns'? I think the chalk was excavated from the pits, brought to the kilns and baked to make cement.

2. The narrow gauge railway I mentioned is marked as 'Tramway'.

3. As for the tunnel, I take it you mean the dashed line. It's a bit too out-of-focus for me to read the lettering but I doubt if there's a tunnel there.

4. Tell what I'll do. I live only two miles from there on Blue Bell Hill, when I have time over the next few days, I'll pop down with both our maps and actually see for myself.

Monday, May 9, 2011

Vacant Situations

A physical resemblance to the principals is desirable but not essential, however the ability to respond intelligently and creatively in discussion, conversation, during interview and other interrogative conditions is essential, as is the ability to be creative and flexible with factual information.

The positions are currently on a voluntary basis, however Sanderson and Ball can offer generous profit-share arrangements on a commission basis to the successful candidates if sufficient finances are secured for the project.

To apply email your CV to the Film of the Same Name Recruitment Office. Due to lack of administrative resources applications will not be acknowledged and contacted only if required for interview. No other correspondence will be entered into.

Tuesday, April 26, 2011

The Vanishing Hitchhiker

- "Ghost of young woman asks for ride in automobile, disappears from closed car without the driver's knowledge, after giving him an address to which she wishes to be taken. The driver asks person at the address about the rider, finds she has been dead for some time. (Often the driver finds that the ghost has made similar attempts to return, usually on the anniversary of death in automobile accident. Often, too, the ghost leaves some item such as a scarf or travelling bag in the car.)"

Monday, February 28, 2011

From the unoriginal soundtrack

Monday, January 31, 2011

Cliffe Marshes 25 January 2011 part 1 & 2

At the top of Church street we turned left past a small cottage which I was assured was once a pub and onto the start of the footpath. The ground was heavily waterlogged from the recent rain and we had walked but a few yards before the path became impassible having turned into a small pond. Alternative routes were sought to the left and the right but here streams were found to block the route. After some deliberation we retreated a short way and entered a field looking for a way round. However after some time spent circumnavigating the field we found our route once again blocked by a stream.

It was felt best to try an alternative path altogether via the church. We retraced our steps through the village, passing a somewhat over excited Alsatian dog whose owner looked on impassively as it barked at us furiously before reaching the level crossing and finally on to the marshes.

We were now not at the beginning of the day’s planned route but rather the end point and so it was agreed we would to try and rejoin the intended path. We climbed a gate and began traversing a field. Overhead were two sets of impressive pylons and a number of telegraph poles. Sanderson had brought along some stills from Green on the Horizon and attempted to correlate the shots with the landscape before us. Meanwhile Ball took out his iPhone which it soon became clear was the only map/navigation device we had.

After some zig-zagging to avoid the more waterlogged parts of the field we found ourselves in the bottom corner close to the original path but with our progress frustrated once again by a stream. This would become a regular pattern throughout the morning, as it would seem that all the fields on the marshes are surrounded by streams or drainage ditches. Each field has one or more gates leading to another similar field. However upon entering the field it is far from clear where the next gate is, if indeed there is one as some fields are effectively islands. On repeated occasions we arrived at the edge of the field within sight of our intended destination but thwarted by yet more water.

This maze like reconnaissance went on for about an hour and a half with much criss-crossing and retracing of steps. We passed through fields of sheep and cattle that looked on bemused at the lack of progress we were making. Sanderson began suggesting that we should perhaps rewind altogether and take the designated footpath. Ball ignored this suggestion but began to spend more time peering intently at his iPhone.

From the estuary wall (also known as the Saxon Shore Way) we could see over to Kings North power station, which was pumping out grey smoke into the already leaden sky. Whilst no doubt environmentally unfriendly it was a pleasing sight. A few yards further on we had an encounter with one of the many Shetland ponies that have now inexplicably taken up residence on the marshes. Sanderson attempted to feed the pony some tangerine but the rather mournful animal was not the least bit interested letting the fruit fall to the ground.

I asked if the new performers, William Fowler and Leigh Milsom would be accompanying us on a future visit to the marshes to re-enact the sequences, but received a mixed response. Ball suggested that yes this was indeed the plan, but the answer from Sanderson was more opaque, creating the impression that perhaps that this was not a trial run but the actual shoot.

We were now by the rear of the fort and at the time of filming over twenty years before, it had been possible to gain entry to the fort through a gap in the fence, indeed there is a shot of ‘the girl’ doing just that. The metal fence was still there, but a further small fence had been added presumably to stop children and filmmakers gaining entry. This was broken down at one point and thinking that this offered a way in we slipped down the bank only to find ourselves ensnared in brambles, and after much muttering about torn clothing it was decided to abandon trying to get into the fort fro today at least, and we began to retrace our steps back towards the railway station. This proved relatively simple compared with our incoming journey, taking less than half an hour. We stopped on the way at the church which as with many village parishes was open, to firstly remove the caked mud from our shoes, and then to record a version of the ‘theme’ from Green on The Horizon,which Ball whistled as he walked back and forth in the resonant space. Back down Church lane and a couple of much needed drinks were had at the Railway Tavern, and then it was off back to London.

Tuesday, January 25, 2011

Monday, January 17, 2011

a straight line is not always the shortest distance between two points

|

| Alfred Watkins |

| |||

| left: frames from Riding Ring, Guy Sherwin, 16mm, 1976 right: the device used to make Stream Line, Chris Welsby, 1976 |

|

| frames from Vertical David Hall, 1969 |